The Book Exodus – being called ‘Shemot’ (Names) in Hebrew – starts out with the following verses:

These are the names of the sons of Jacob, each with his own household: Reuben, Simeon, Levi and Judah, Issachar, Zebulun, and Benjamin, Dan and Naphtali, Gad and Asher. All the descendants of Jacob were seventy persons; Joseph was already in Egypt.[1]

Jacob and his sons went to Egypt because of a famine in Canaan where they used to live. They stayed in Egypt for several generations, and remarkably, during all that time they kept their own language, their way of dressing and their Hebrew names. Names are very important in Judaism – they are part of a Jew’s identity, and the name that parents choose for their child, is even said to be a small prophecy.[2]

After the expulsion from Judea that began in the year 70 AD, the Jews – living from then on in the diaspora – kept their language, clothes, and names for centuries. However, between the ninth and twelfth century, Yiddish became the lingua franca of the Jews who lived in Central and Eastern Europe. The base of Yiddish being the German language of those days, many Hebrew words were added as well as elements from Slavic and other languages. However, being written with Hebrew letters from right to left, Yiddish was still a genuine Jewish language.[3]

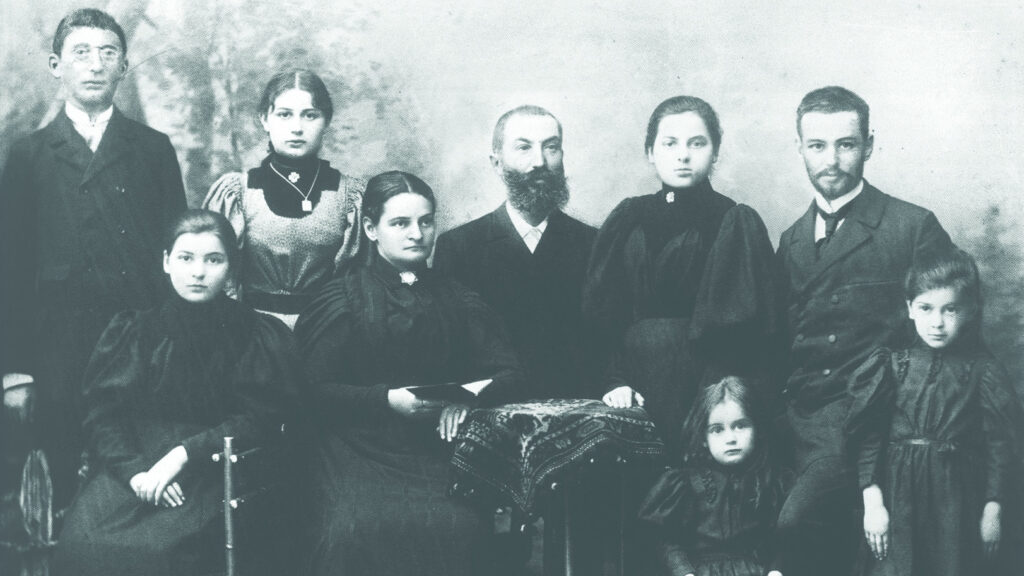

In the nineteenth and twentieth century in Breslau, German-born Jews like the Stein family did not speak Yiddish; their mother tongue was German. The Steins were not particularly religious and hardly ever attended the synagogue service, not even on a Sabbath. On High Jewish festivals Auguste Stein used to go to synagogue, but she usually went by herself. However, the younger generation in the family still enjoyed lessons in the Jewish religion, taught by the liberal Rabbi Vogelstein. Auguste’s sons probably knew enough Hebrew to say the blessings before the Sabbath meal, when the family came together, but none of them was fluent in Hebrew except for Frieda’s daughter Erika who eventually turned into an observant Jewess. Both men and women in the bigger Stein family at Michaelisstrasse dressed like the rest of the Germans. Neither Else, Frieda or Erna Stein nor Arno’s wife Martha or Paul’s wife Gertrude would cover their heads with scarves let alone wear a ‘scheitl’ (wig), as observant Jewesses do when being married. The Steins were clearly assimilated Jews. Their Jewishness was on a steadily falling level, and yet, they still had a Jewish identity. They held fast to basic Jewish dietary laws and presumably to circumcision, and none of them intermarried with Christians.

What about their names? The family name Stein is not typically Jewish like the names Cohen or Süsskind, as many Christian families bear the name as well. This seemed helpful in case one was interested in assimilation. As to the first names, assimilated Jews often chose names that sounded altogether German, presumably in the intention not to immediately reveal their Jewish identity to prevent discrimination. However, the unobtrusive first names that were popular among Jews were often similar to Hebrew names in letters or sounds, and thus – regardless of their original etymology – they would assume a different meaning in Jewish ears.

The name Else, pronounced with a voiced ‘s’, corresponds to the Hebrew name Alizah, whose Hebrew root (עלז) makes us think of a ‘cheerful’ girl. Alternatively, we may think of Elisabeth, which would be Elisheva in Hebrew, being interpreted either as God of Oath, as My God is Seven or even as God is Abundance (Eli shefa).

Elfriede – abbreviated to Frieda – is a combination of a Hebrew term for God (El) and the German word for peace (Friede), so the meaning may be God is Peace. Peace – Shalom – is a male name in Hebrew, whereas the female equivalent would be Shlomit or even Shulamit. As there is also a reference to peace in the name of Siegfried Stein, we may ascribe the male name Shalom to him.

The name Erna is similar in letters and sound to the Hebrew name Orna, which is a feminine form of the male name Oren, referring to a pine tree. Arno has the same Hebrew root as Oren, but it is also close to the male name Arnon, being the name of a brook in Israel.

Paul shares three letters with the Jewish name Saul, and here the Apostle Paul comes to mind who used to be called Saul, being a son who was ‘asked for’. Is it coincidence that Paul Stein’s full name was Paul Salo Stein? Salo reminds us vaguely of Saul, but we also think of the name Salomon which is related to the names Shlomo and Shalom, meaning peace.

Rosa refers to a rose flower, which in Hebrew is Vered, and to the colour pink which is ‘varod’ in Hebrew. However, in German ears the name Rosa still sounds very Jewish, perhaps because the name was especially popular among Jews, other than the name Rosemarie that the Jews apparently did not care for. Many Jews refer to a rose by the Hebrew term Shoshanah which is actually a lily. This is a beautiful, but rather old-fashioned female name today and corresponds to the name Susanne, and here Erna’s daughter Susanne Biberstein comes to mind.

It may be of special interest if the name Edith has a Hebrew connection. In Yiddish, the name Judith is pronounced as Ides or Yidiss, referring to a Jewess, and this what Edith Stein was: a born Jewess.

[1] Exodus 1:1-5. Quoted from: Holy Bible, English Standard Version (ESV), London 2017.

[2] Rafael Evers (chief rabbi), Schmot: Leitung und jüdische Identität, in: Raawi, Jüdisches Magazin. Online available under https://raawi.de/schmot-leitung-und-juedische-identitaet 1.

[3] Universität Trier, Was ist Jiddisch? https://www.uni-trier.de/universitaet/fachbereiche-faecher/fachbereich-ii/faecher/germanistik/professurenfachteile/jiddistik/intensivkurs-jiddisch/was-ist-jiddisch 1